I find it quite stimulating to alternate between working on completely new pieces and revising or reworking older ones. Returning to older pieces like this renews my appreciation of my previous works, at the same time as it highlights my continued development as a composer.

There is a potential danger, or at least a problem, with constantly revising one’s work. At some point you have to say ”enough” and leave what has been written behind to concentrate on making new music. On the other hand, with more experience I also better understand how to convey my ideas more clearly in writing. Additionally, I feel that some of my older pieces have benefited from what I might describe as an extended gestation period, and having left them for a year or two I very clearly see what they have been missing.

I have always worked relatively fast when composing, working out ideas in my head in between writing sessions at my computer or on paper. Sometimes, the resulting composition ends up being more or less fully formed and even looking at it later I don’t see the need to change anything. Other times, upon later inspection it is clear that the piece needed a little more time in the proverbial oven.

In the last seven or eight years or so, I would say that later changes have become much more infrequent and minor than what they used to be. Often it simply comes down to more elegant or precise notation, rather than changing the musical material itself.

In 2018 I composed Trinidad for violin duo, written for and dedicated to the inspiring Weber Duo. I even wrote about the premiere performance in Härnösand in one of my first blog posts.

Last October, I returned to the piece and made a number of light revisions. Many were simply notational edits and the changes to the music itself were all rather small. I wrote the piece specifically with Ronnie and Ellinor Weber in mind. I wanted it to reflect their enthusiastic and highly skilled musicianship as well as to take as much advantage as possible of their instruments.

Over the past month I have been working on a brand-new version of the piece: Trinidad for saxophone quartet. I have recently gotten to know the Stockholm Saxophone Quartet, and especially their alto saxophonist Jörgen Pettersson, and we have been talking about working together. Not having written anything for saxophone quartet before, I wanted to practice on something and quickly thought of Trinidad.

Much like Ronnie and Ellinor, the members of the Stockholm Saxophone Quartet are not only amazing musicians but also brilliant and expressive performers that are not only a joy to hear but also to watch. The idea behind Trinidad – working a Caribbean rhytmic style into a Western classical idiom – also felt to me like it would fit a saxophone quartet setting like a glove.

And I really do mean that this is an entirely new version of the piece, not just an arrangement. In the original version, the two violins often play more than one note at a time using double (or even triple) stops. The four saxophones, on the other hand, are essentially limited one note at a time. However, having four separate players opens the door to more complex part-writing.

In other words, while it was mostly easy and fun to adapt the piece to this new ensemble, I both had to and also wanted to make several changes to it in order to better suit the new instruments. Rather than simply copying and pasting the music from one setting to another, I made an effort to work the saxophone version into its own thing so that neither version of Trinidad supplants the other.

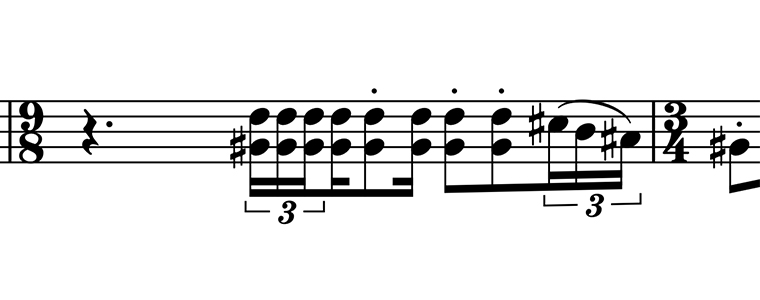

Compare the two excerpts above. The left image shows the original violin part: the repeated 16th triplet on the second beat is no problem to pull off, and the descending figure leading into the next bar is a single melodic line. The right image shows the corresponding music played by soprano and tenor saxes: because repeated notes are very difficult to play on a saxophone, the first 16th triplet is now a slurred, ascending figure, and each player gets their own figure leading into the next bar.

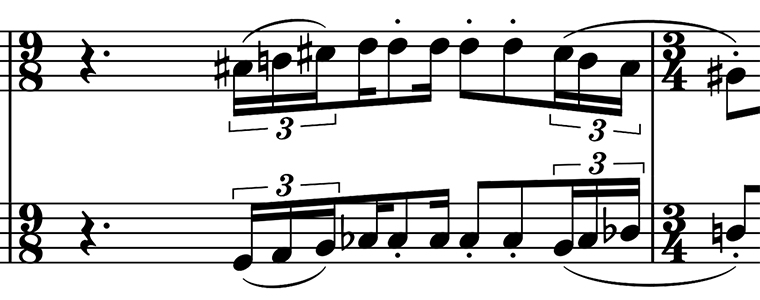

Below is another excerpt. The top image shows the original violin part: switching between the different double stops is the challenge here, while the repeating figure itself is simple enough to play. In the bottom image, the same music is written for soprano and alto saxes: besides having to split the two-note accompaniment between two players, I have had to include rests to account for the simple fact that the players will eventually have to take a new breath.

This particular excerpt also presents a situation where practical needs meet aesthetic choices. I could easily have fewer and more spaced out rests than I do here. This second example i also taken from a longer section with the same kind of accompaniment. (In the original version, there are no rests since the violinist is able to breathe and play at the same time.)

Now, instead of simply trying to keep the number of rests to a minimum, I decided to try and incorporate the breaks natuarlly in the music. Hopefully then it sounds less like a choice borne out of necessity but rather one made with an aesthetic idea in mind. Of course, if I had originally written Trinidad for saxophone quartet rather than violin duo, this section might have turned out different altogether.

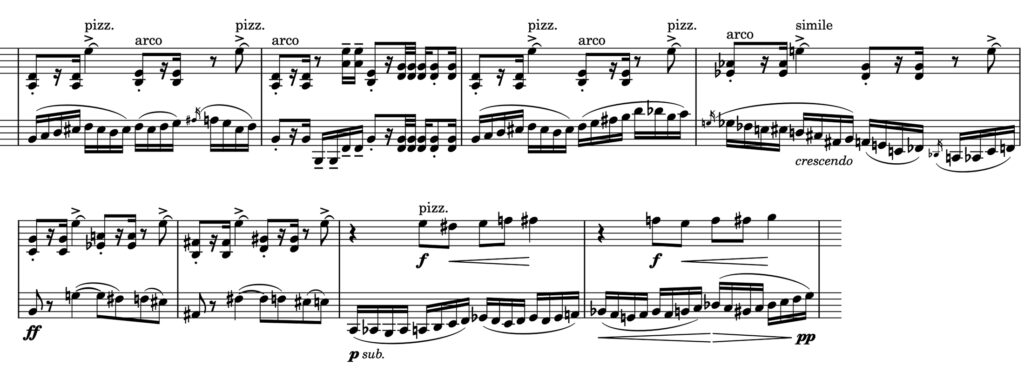

Let me show you one final example from the final section of the piece. In the original violin part, one player alternates between playing a bowed rhythm and plucking the open E string. I was in part inspired by the typical kick/snare drum beat, with the pizzicato acting as the snare drum. Incidentally, this kind of writing also resembles a cappella arrangements of pop music which is another one of my specialties. The melody is a virtuosic whirlwind, interrupted by a ff (fortissimo) statement of the main theme of the entire piece.

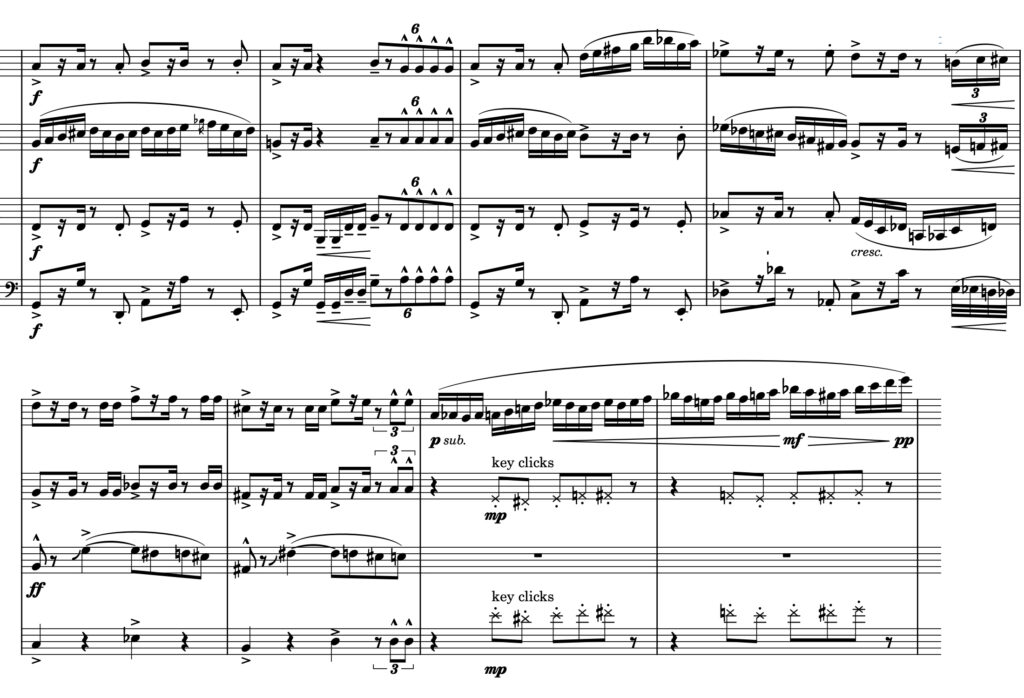

This section is rather more developed in the saxophone version, owing to the doubled number of players. The melody wanders between the soprano, alto and tenor saxes, with the ones not currently occupying the melody playing the accompaniment. Also notice that, in the second bar, the rhythmic flourish in the violin version with 32nd and even 64th notes is turned into a juicy sextuplet stab figure that also adds rhythmic interest to the music by breaking up the 16th note subdivision of the regular accompaniment.

In the final two bars, I substitute the original version’s pizzicato with a special playing technique that makes a sound that if not similar then is at least pizzicato-adjacent. And that elegant, flowing melody will sound delicious played by the soprano saxophone. Note that in this example I have written the baritone saxophone in a bass clef (all others are written in treble clef). The alto, tenor and baritone saxophones are all transposing instruments but the examples above are all written in concert pitch, i.e. as they sound.

First impressions from Jörgen, whom I have shown early drafts, have been very positive. I can’t wait for the whole ensemble to try the piece out. Ronnie and Ellinor have really taken to Trinidad, which makes me very happy. I hope that the saxophone quartet will as well.

Last week, I told you I would also discuss the reworking of my Christmas oratorio as well as (maybe!) Something Else. Both of those things will have to wait another week, but I do hope you enjoyed reading this rather extensive presentation nevertheless. See you next week!