I feel like this week hit me like a sledgehammer! Monday feels like it was only yesterday, even though it was actually three days ago. Madness. And I feel like I have spent most of the week so far writing and replying to an endless number of emails.

I started the week off by getting my Covid booster shot, followed by this year’s first lecture on Western Music History, which was lots of fun! (The lecture moreso than the shot, obviously.) For last year’s lectures, I started off in the 20th century and went backwards, tracing the musical landscape of today through our musical history. This year I started out back in Ancient Greece – actually, as far back as the Mesopotamian civilisations! – and will now continue in chronological order, in more typical fashion.

Based on my experiences from last year and the feedback I’ve received both from students and from peers, I feel increasingly more certain that this is a pretty neat setup. Most students at the folk high school where I teach take two years, so regardless of which year they begin the will get one year in chronological order and one in reverse.

Each year brings a different perspective, so that even though many things will be repeated (not that repetition is necessarily a bad thing), events and developments will be presented from slightly different angles.

In preparing my material, I am striving for a two-thirds split, approximately, where somewhere between half to two thirds of the information I bring up is essentially the same between both years. To some of you this might seem like poor use of time. But this is a very conscious choice on my part.

Most of these students come straight out of high school and most don’t think of music history as being the most exciting thing ever. I know I cannot expect them to do much work on their own outside of my lectures, so in this format I feel I will be able to best teach and engage the biggest number of students. So far it seems to be working really well.

I have already planned out my next lecture. I decided to spend a generous amount of time discussing not only the development of music but also the surrounding political and social factors that contributed to the way music developed in the western world. For example, the Hellenistic period during which Ancient Greece also became part of the Roman Republic. And later, when Nicaean Christianity became the state church of the Roman Empire, which led to Christianity’s dominance in the western world.

By the way, did you know that two fairly complete and intact Hellenistic hymns dating back to 128 BCE were discovered at Delphi in the late 19th century? And did you know that Gabriel Fauré was commissioned to arrange one of the hymns, which was then published as Fauré’s ”Hymne à Apollon”? And did you know that there have since been more authentic performances of the original hymn?

Anyway. Having gone through all that, I can start talking about monasteries where monks and nuns were taught reading and writing, farming and of course music; about Pope Gregory I who made several important liturgical reforms and who is said to have compiled an “annalis cantus omnis”, an early attempt at a collected repertory for the entire liturgical year.

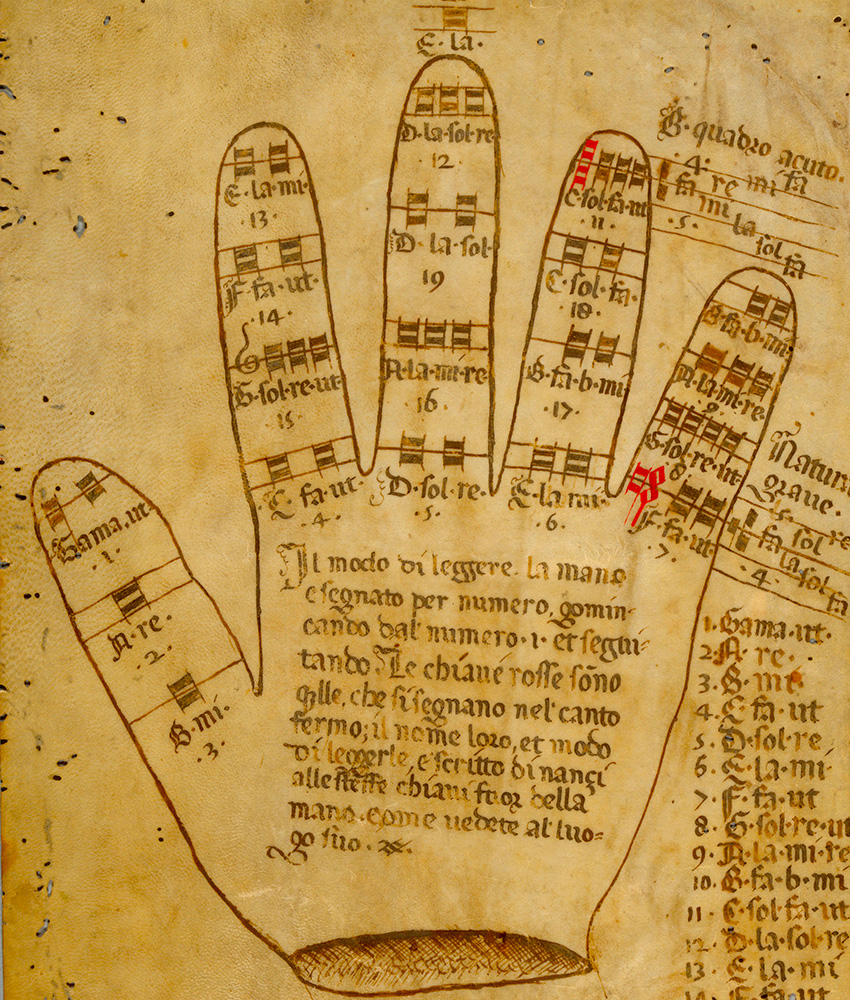

From there on, it’s all about the early Western notation system using neumes, which over the course a few hundred years grew into an basic version of the notation system we still use today, credited traditionally to the influential 11th century musical scholar Guido of Arezzo.

It has been a busy week, basically. This is not even all I’ve worked on since last week’s post. Another of the more exciting events was rehearsing with Matti, my wonderful pianist, ahead of our upcoming recital “Songs About Death and Life”.

Tomorrow, at least, I will finally have time to continue preparing score materials for the new, reduced instrumentation version of my Christmas Oratorio. I will also spend some more time at the amazing organ of Härnösand Cathedral, working out different registrations. It is doubly rewarding, both as a kind of musical-practical puzzle and of course as a purely creative process also.

Reducing the instrumentation down to only flute, trumpet, percussion and organ was also a kind of musical puzzle in its own way. In the reduced version, the organ player also has to perform the duties of the string quintet as well as, in a few cases, the second trumpet and the clarinettist in the original version.

The flute and trumpet parts in the reduced version have also been augmented with elements from the clarinet and second trumpet parts, respectively. Also, I have completely revised the two percussion parts, ending up with a much cleaner percussion score than before. The new percussion score also works for both the reduced and complete instrumentation versions, with a clear plan for the principal percussionist and a second ad lib. percussionist when available.

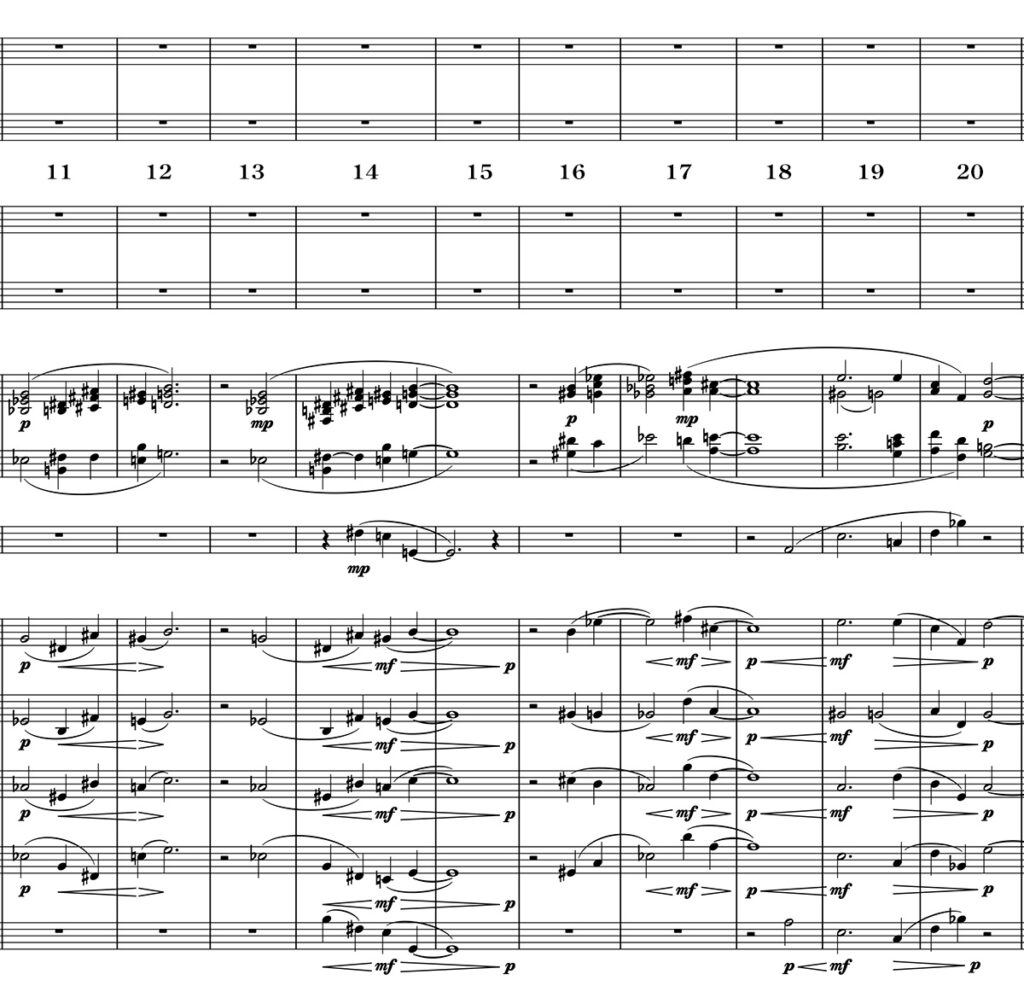

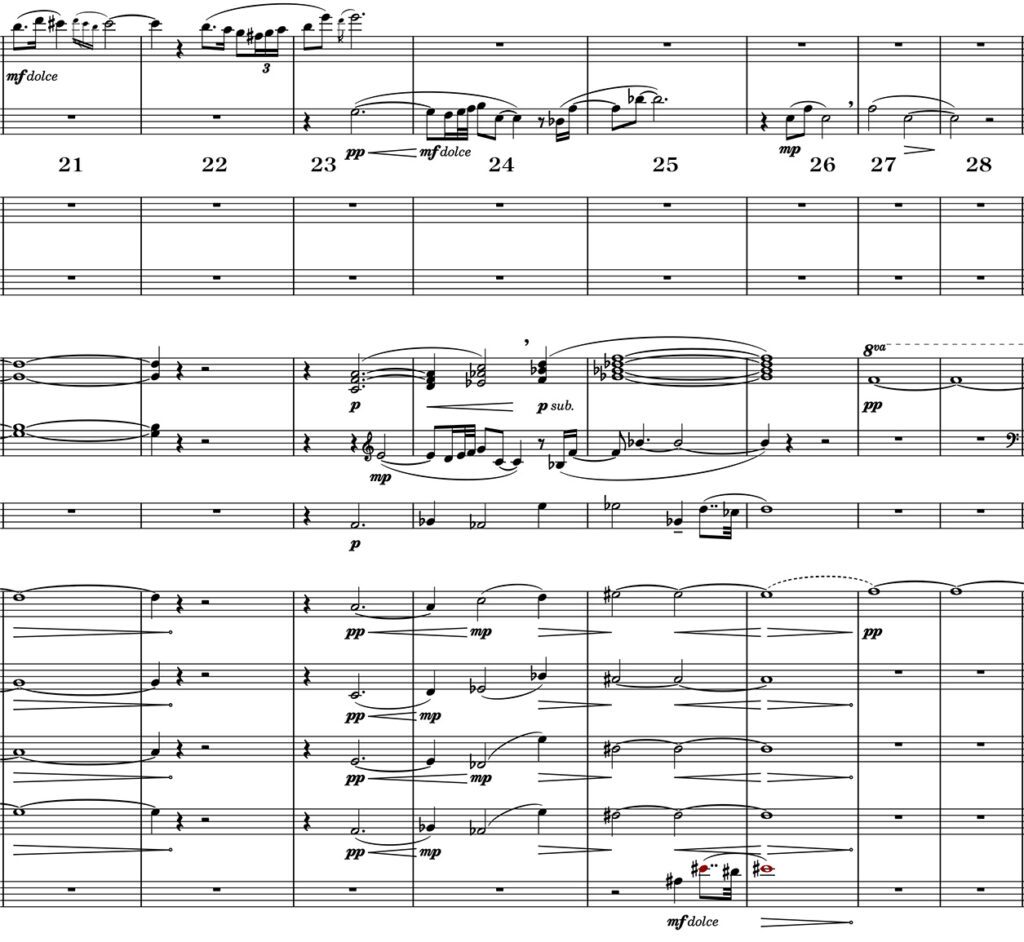

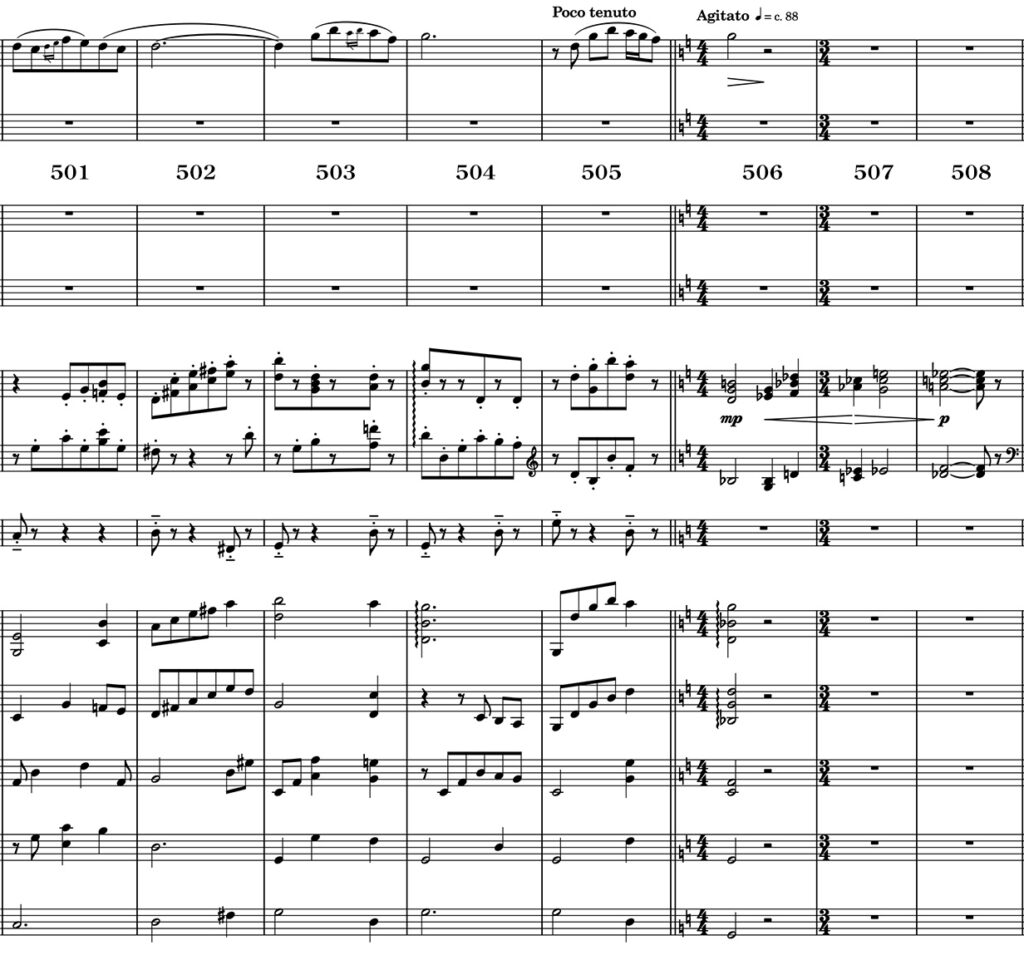

Most interesting to look at here, though, is the organ part, as that is the one that has seen the most changes. Take a look at these 24 bars from the first movement. The organ part comes from the reduced version, while the other parts are taken from the full version, for comparison’s sake. The score order is, from the top: Flute, Clarinet, Trumpets 1 and 2, Organ, Violins 1 and 2, Viola, Cello, Double Bass.

In the original version, the organ was silent here. In the reduced version, the flute phrase in bb. 21–23 remains, while the organ plays the clarinet’s response in bb. 23–25 in the left hand. The last bit of the clarinet line, bb. 26–27, has however been moved to the flute.

The tremolo string parts in bb. 29–35 have been moved up to the organ’s left hand and pedals. (You might just recognise the melody in bb. 29–30 if you read last week’s post…) The swell effects in the two trumpets didn’t have to be sacrificed; they were in fact moved to the one trumpet and the flute. The flute sounds entirely different from a muted trumpet, of course, but the effect is maintained.

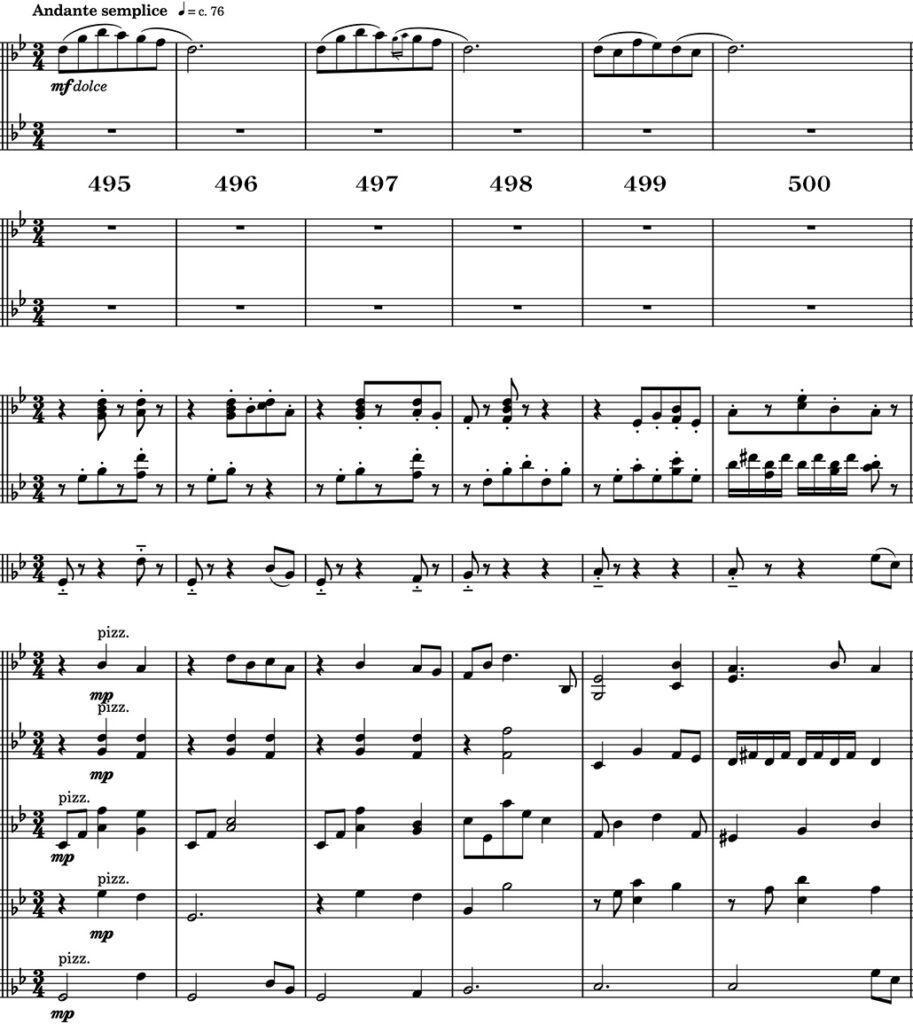

Here is another example, the first 14 bars of the sixth movement. In this case, I had to try and realise the strings’ pizzicato accompaniment in the organ. Incidentally, this is one of the sections that I will look at tomorrow to find a suitable registration.

The difficulty here is twofold: first of all, to write a suitably playable organ part that keeps as much as possible of the string parts, and now to find a good combination of stops for a sound that is a fair substitute for pizzicato. I will not be able to accurately replicate a pizzicato sound, of course, but I need to find a patch that is delicate but has enough attack for the short notes.

In the old version, there was actually another bar between bars 505 and 506 here. The idea was that the flute melody (which is present in both the full and reduced revised versions) would land before the new, discordant section begins. However, the jarring effect becomes even stronger if the mellow flute melody gets interrupted like this. The organist also has time to change to a different registration on the final eighth rest in bar 505.

Well! This turned into yet another incredibly long blog post! I hope you enjoyed reading it, belated as it was. See you again next week, dear reader.

One comment

Comments are closed.