Among my clearest memories from when I was a teenager is a recurring, tangible anxiety over my then current as well as future abilities as a composer. Yes – I started worrying about such things early, why wait?

One of my biggest concerns was that I did not know how to write anything that was longer than about two minutes long. I remember the first time I finished a composition more than three minutes long – what a distinctly middling cause for celebration it was.

Looking back, what I had not yet figured out, or had anyone tell me about, was making variations on whatever melodies or themes I came up with. I was kind of like a poor-man’s Tchaikovsky: repeating my melodic phrases once or twice, before introducing another melody and playing that a few times, and then returning to the first melody.

Yes, I know that what I described is basically ternary form, which is one of the oldest, most well-established musical forms in the entire Western canon. But, few of my melodies back then were really any good, and a decent number of variations might have gone some way to make up for that. Really, what I usually managed was more akin to the first section of a piece in ternary form: not so much A–B–A as A1–A2–A1, i.e. only a third of a complete composition…

One day, I might dare post one of my childhood pieces. Let me know if you absolutely would like that, dear reader, and I might do so sooner rather than later.

Last summer, as recurring readers might remember, I put myself to the test and succeeded in writing two brand new compositions in a little over a week, for two different competitions. One of them, “Skule Overture” for band, was even named one of five finalists out of more than 100 entries in the Grimethorpe Colliery Band Composers Competition!

In this significantly more in-depth blog post, I want to use that piece as an example of how I have learned to use musical development, instead of simply repeating – or replacing – my ideas. Additionally, this skill dovetails neatly with another: knowing how many times to present each idea before actually moving on. It is neither good to repeat the same thing ad nauseam, nor to hurry on before giving what you’re doing at the moment enough time in the spotlight.

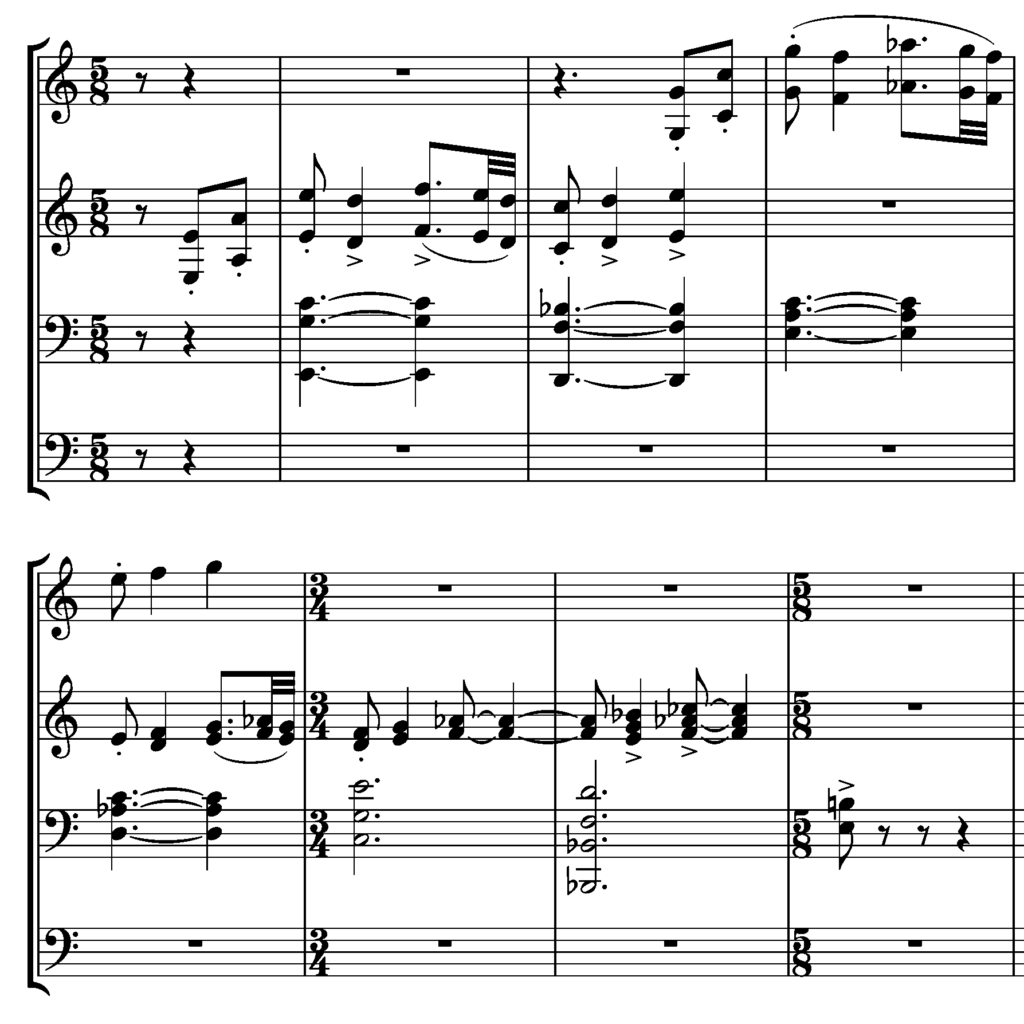

If you want to follow along, I’ve prepared this score reduction for you to download. To reduce clutter, I omitted dynamics and specific instrumentation information, but I have split the music up onto four staves to give an indication of instrumental grouping.

You can also listen to this MP3 recording exported from Dorico 5 with NotePerformer. I hope to get a proper recording of the piece in the future, but in the meantime, this will have to do.

Here is a table I have put together showing the structure of the entire piece. I’m going to go through all of the sections individually below, together with some illustrated examples.

| A1 | A2 | B | C1 | C2 | C3 | D | E1 | E2 | A1* | A2* | Fin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bb. 1–18 | bb. 19–37 | bb. 38–51 | bb. 52–62 | bb. 63–73 | bb. 74–99 | bb. 100–120 | bb. 121–146 | bb. 147–170 | bb. 171–188 | bb. 189–204 | bb. 205–218 |

| 18 bars | 19 bars | 14 bars | 11 bars | 11 bars | 26 bars | 21 bars | 26 bars | 24 bars | 18 bars | 16 bars | 14 bars |

| ♩ = 120 | ♩. = 48 | ♩ = 80 | ♩ = 96 | ♩ = 120 | |||||||

| Excited | Mysterious | Muted | Heroic | Excited | |||||||

This is the primary motif, introduced at the start of the piece. It forms the basis for almost every other bit of music in it.

The A section of “Skule Overture” is made up of two main subsections – let’s call them A1 and A2. Each subsection presents the primary motif twice, followed by an interval – which is based on the primary motif – and then repeats that three-part structure again. The first interval only two bars long; the second interval, which leads into A2, is twice as long, giving it more time to grow.

A2 is structured identically to A1, but with altered instrumentation and some added details in the arrangement. A2’s second interval is even longer still: seven bars of build-up, ending the A section with a dramatic fortissimo tutti.

Originally, I didn’t have two subsections in A; my first version of A was kind of like the first half of A1 and the second half of A2. But while working on the B section, I felt that having an A section that short made the piece lopsided, so I made myself go back and extend the A section.

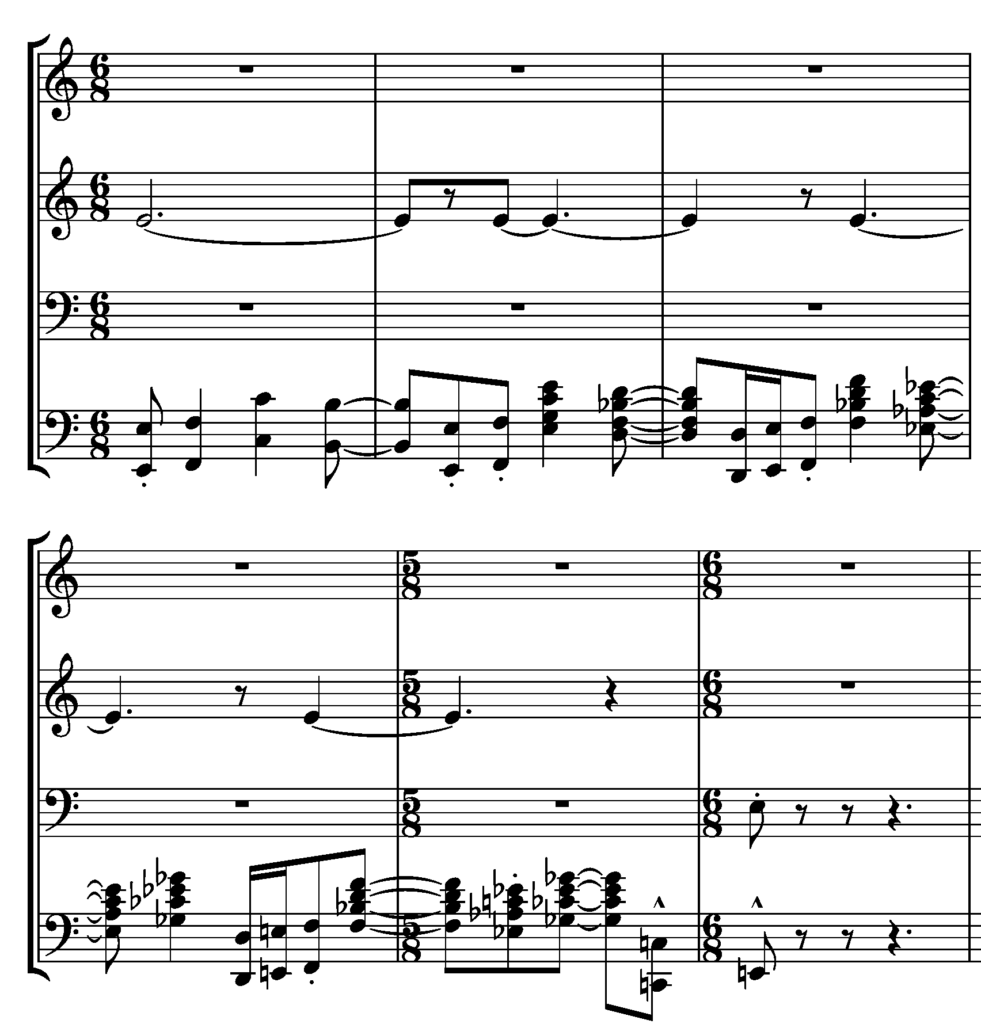

The B section is fairly short, with three statements of the same idea, each one a little more developed than the former.

The first statement is played by low instruments, trombones and tubas, with very few 16th notes; the second statement adds horns and flugelhorn an octave above and a distinctive 16th note run; the third statement supplants the low instruments with high cornets and adds further embellishments.

The first version of the B section had only the first and third statements, which felt fine, but after extending the A section it was rather dissatisfying. Adding a middle statement brought back balance to the piece’s progression.

The C section has three subsections – C1, C2 and C3, naturally – growing in intensity with each new section. C1 begins the C section with the flugelhorn and two baritone horns playing the C section melody in octaves to a 16th rhythm accompaniment in the (French) horns. The accompaniment figure is lifted straight out of the primary motif, but given a new, more mellow identity. The C section melody is also based on the primary motif.

Note that in both C1 and C2, the melody’s second entry is shifted one eighth note: The third note in the “dat dat daaa” sequence is syncopated in the first entry, but lands on the beat of the next bar in the second.

C2 exchanges baritone horns for a couple of cornets and euphonium for a stronger, brighter sound with more of the upper octave. A brief variation complete with snare drum and timpani segues into C3 with trombones and baritone horns laying the foundation and both cornets, horns and flugelhorn playing the C melody together.

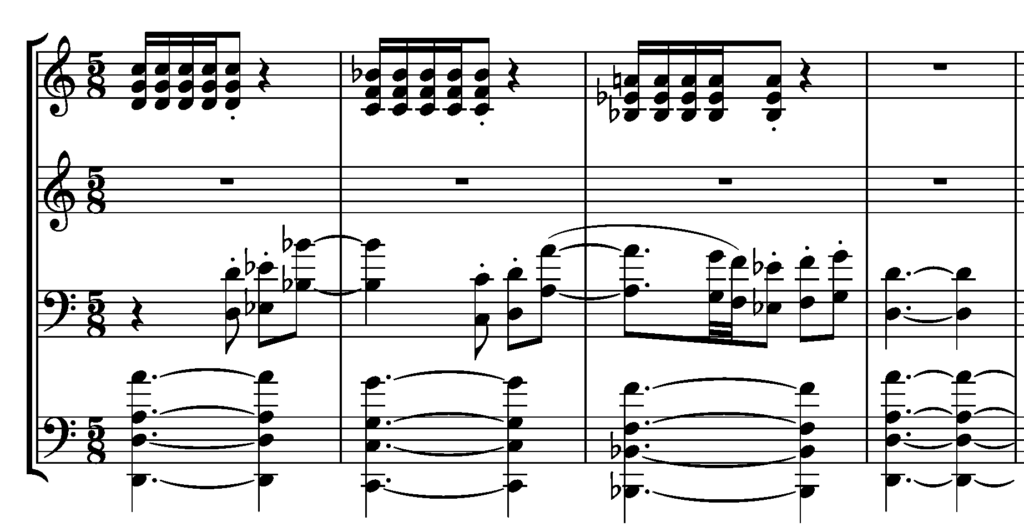

C3 builds to the first major climax of the entire piece, with various statements – a variation on the C section material – occurring three times (have you noticed the pattern yet?), slowly taking the piece down again to the D section:

D begins with that profound A in tubas and bass trombone, lingering on from C3, against a wistful flugelhorn solo that develops into four-part counterpoint together with cornet, horn and soprano cornet. The D section melody is also a variation on the primary motif, but adjusted in such a way that it is also reminiscent of the overarching melodic theme of one of my larger compositions. (Email me if you think you know which one!)

The E section is divided into two subsections quite different from each other, but united by the same melody. The E section melody is the one farthest removed from the primary motif; I don’t remember what inspired it, but I think it was simply a case of coming up with something that both fit the tone of the music and sounded good together with the existing material.

Going back to the Tchaikovsky analogy earlier, I do think that one of my strengths as a composer is an affinity for melodic writing. Part of that, I think, is thanks to a healthy diet of quality game music growing up. Tchaikovsky obviously didn’t play video games, but he sure could write some fantastic melodies.

A soft timpani roll on A bridges the D section’s A major tonality and A minor in E1, with the flugelhorn introducing what becomes a wistful, melancholic quartet. (Chamber-like counterpoint writing is a common feature of the D and E1 sections. This was a deliberate choice, to further emphasise the difference between the big tutti sections and these two more intimate ones.)

At the end of E1, a stepwise falling bass tone and some colourful chords lead into the far more optimistic E2, where the the E section melody is reinterpreted in a more heroic, film-score-like fashion. E2 also adds the primary motif as a bright countermelody in octaves: in soprano cornet, flugelhorn and glockenspiel. (This not only fits musically, but also plants the idea that we are about to return to familiar territory…)

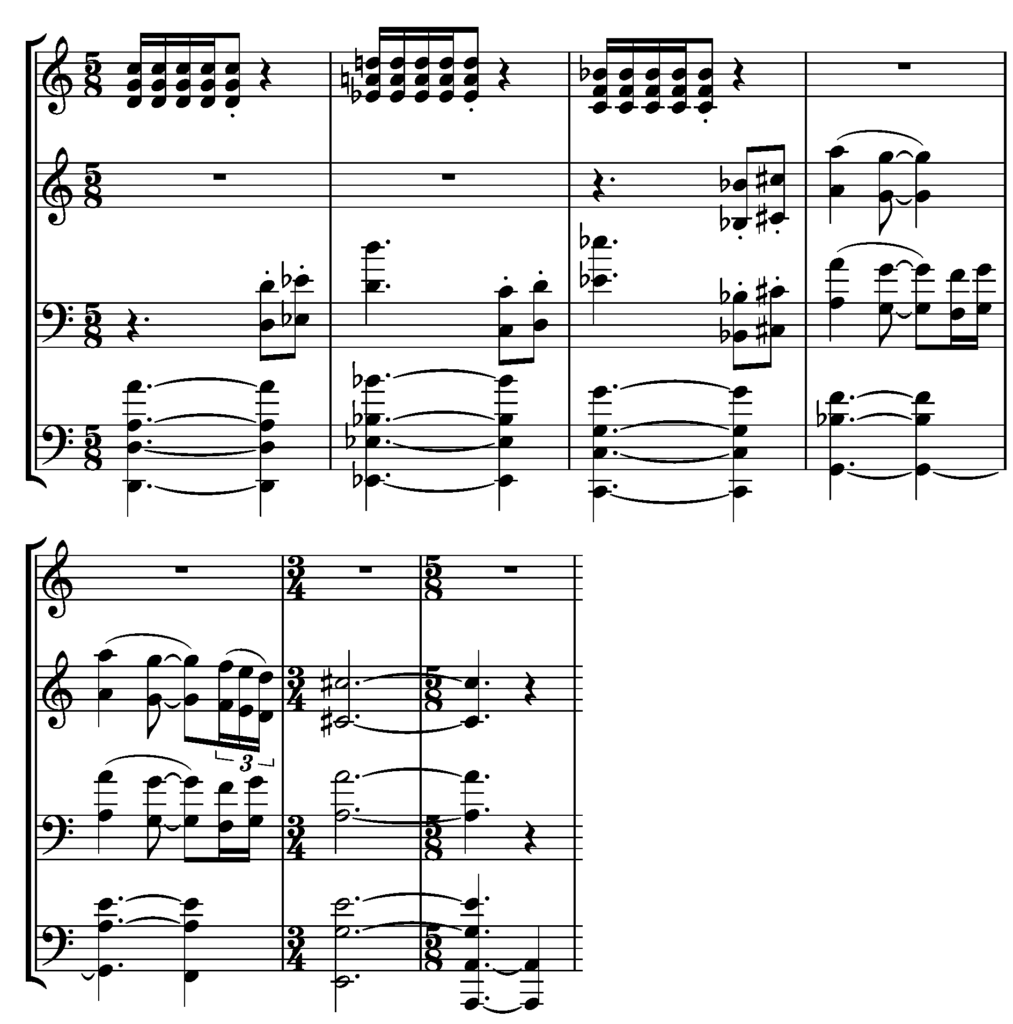

E2 then builds to a powerful transition, where the primary motif gradually mutates back into shape, harmonically going from F major through D minor and back to the Esus tonality of the A section.

In other words, it is time for a da capo! A1 is identical to the start of the piece. The instrumentation in A2 is however changed slightly, and A2’s second interval this time leads into a brand-new coda, where the interval motif is turned into a fanfare, which finishes the piece with what at least to me sounds kind of like a John Williams rhythm: “dja-ga-dam, dja-ga-dam”!

I remember fretting about how to wrap the piece up. I considered a much softer ending, kind of like how the D section ends, which would have been more unexpected than going out with a bang. I still nurtured this idea while working on the E section, but when I was mostly done with E2, I was far too happy with how it turned out to take it out again in favour of a different ending.

Finally, here is once more the table showing the entire structure of the piece. I didn’t have a plan going in, so the piece essentially took shape while I was writing. I ended up with a pretty well-balanced structure, though, thanks to the fact that I kept reevaluating how what I had just added to the piece did for what came before.

| A1 | A2 | B | C1 | C2 | C3 | D | E1 | E2 | A1 | A2* | Fin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bb. 1–18 | bb. 19–37 | bb. 38–51 | bb. 52–62 | bb. 63–73 | bb. 74–99 | bb. 100–120 | bb. 121–146 | bb. 147–170 | bb. 171–188 | bb. 189–204 | bb. 205–218 |

| 18 bars | 19 bars | 14 bars | 11 bars | 11 bars | 26 bars | 21 bars | 26 bars | 24 bars | 18 bars | 16 bars | 14 bars |

| ♩ = 120 | ♩. = 48 | ♩ = 80 | ♩ = 96 | ♩ = 120 | |||||||

| Excited | Mysterious | Muted | Heroic | Excited | |||||||

To summarise, there is plenty of repetition in “Skule Overture”, and most of the piece is based on a single musical idea.

In hindsight, while I do think that I did quite a good job developing this principal motif throughout the different sections, I kind of also feel like I got lucky in that the idea turned out to be quite malleable and easy to adapt to different uses. Not all ideas are as easy to work with, but I do think that, on principle, pretty much any musical idea can be used as raw material for a whole range of themes and motifs.

Teenage me would have been so proud.

Oh, and yes – ”skul” is an ancient Swedish word for ”shelter”. The piece is named after the Mountain of Skule, a local landmark not at all far from where I live, a World Heritage site, and a beautiful hiking destination.

2 comments

Comments are closed.