The other day, I stumbled on a quote by composer Alfred Schnittke which I sympathised with quite a bit. It is important to try and avoid projecting yourself onto someone else without a deeper understanding of who that other person was (or is), but in meditating on that quote, I felt I came a little closer to my own perspective on music.

Now you might wonder how the title of this post relates to Schnittke. And, well, it doesnt’t. But I’ll get back to that a little bit later.

Anyway, this quote comes from a 1996 biography on Schnittke written by cellist Alexander Ivashkin, who worked extensively with him and other contemporary composers. Schnittke, who was born in Soviet but with a German heritage, studied music in Vienna in his youth. The quote relates to Schnittke reminiscing about his time in Vienna and a sort of epiphany that came to him there:

I felt every moment there, to be a link of the historical chain: all was multi-dimensional; the past represented a world of ever-present ghosts, and I was not a barbarian without any connections, but the conscious bearer of the task in my life.

Alfred Schnittke, quoted in ”Alfred Schnittke” by Alexander Ivashkin (Phaidon Press, 1996)

Ivashkin further describes the teenage Schnittke as falling in love with music as a part of life, both in the sense of music as something alive in the present and as the living past speaking to us through written scores and writings on or about music in ages past. This holistic perspective, as I interpret it, is something that I also identify with.

Schnittke had several different phases in his career a composer. He started out a kind of neoromantic composer, with influences from his prominent countryman Shostakovich. He had a brief serialist period, inspired by Italian avant-garde composer (and devoted Marxist) Luigi Nono’s visit to the USSR. Famously, Schnittke fell out of love with serialism, self-depricatingly describing his foray into serialism as ”puberty rites of serial self-denial”.

Towards the end of his life, Schnittke wrote introspective, austere works, often on spiritual themes – he converted to Roman Catholicism in the early 1980s – but it is probably the works from his third phase that are the most famous. Beginning in the 1960s, Schnittke developed a kind of polystylistic idiom that takes music from several different styles and periods and combines them in a way that might appear to the untrained ear as a sort of chaotic musical patchwork quilt, but is actually quite meticulously constructed.

In a similar way, but with a result that sounds entirely different, Arvo Pärt’s superficially simple works like Spiegel im Spiegel or Fratres are looked down on by their detractors as little more than elevator music, but there is a precision and artistic craftsmanship to Pärt’s music that his copycats and unwilling interprets do not, or can not, see.

Compare and contrast, if you will, the wild ride that is Schnittke’s hour-long Symphony No. 1, with Pärt’s aforementioned Spiegel im Spiegel for piano and violin. Schnittke quotes Tchaikovsky, Strauss, Haydn and Chopin, includes a chamber music interlude for violin and piano, a jazz ”improvisation”, and often plays several different ideas and quotes at the same time in a manner similar to Charles Ives (but for entirely different reasons).

And from that riotous cacophony, to utter stillness.

Earlier this year, Arvo Pärt was awarded the Polar Music Prize: ”Pärt has likened his music to white light. It is in the encounter with the prism of the listener’s soul that all colors become visible. Anyone who has heard his laconic, reduced compositions will understand this perfectly. […] Arvo Pärt’s courageously beautiful music creates depth in every sense.”

Alfred Schnittke was not honoured in such a way, and perhaps a hundred years from now his music will have been mostly forgotten while Pärt’s still survives. But Tom Service wrapped his guide to Schnittke in The Guardian up in a delightful way: ”the real legacy of Schnittke’s music lies precisely in its multidimensional exploration of what musical truth in the 20th century might be, from chaotic polystylism to heartfelt spirituality – and everything in between.”

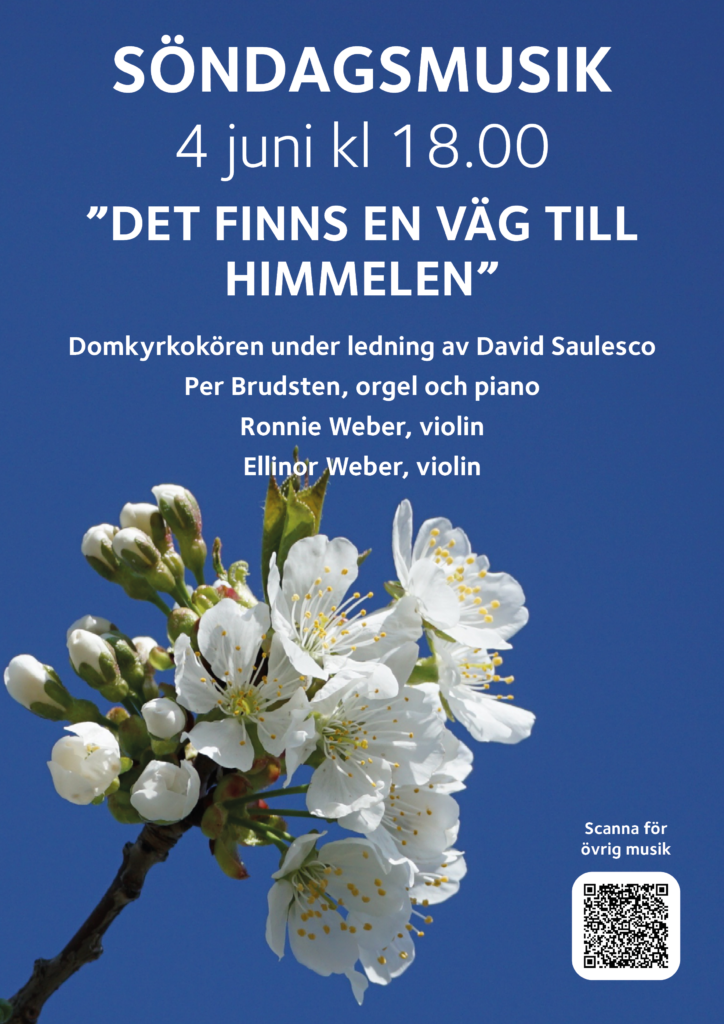

Now, with that out of the way, what did I refer to in the title of this post, anyway? Well, as I described in my previous blog post, I am rehearsing with the Härnösand Cathedral Choir for our upcoming concert on June 4th. This past weekend, after giving it much thought, I decided to remove one of the pieces from the programme.

The decision was that much harder to make, because the piece in question was one of my personal favourites. But I simply don’t think we would be able to get it to the point where we would be able to represent it properly in a concert. Therefore, we would be better served by devoting more time to the other pieces, rather than spreading ourselves too thin.

It is such a delicate balancing act, frustrating and rewarding, to assemble a well-balanced concert programme. Still, even without this particular favourite of mine, the concert is shaping up to be something special, I hope. If you happen to be in Härnösand that weekend, I hope I will see you there! There is even an event on Facebook, if that’s your thing.