Even if you know me only superficially, you might very reasonably assume that my life is always full of music. Inasmuch as that may be true, this weekend ended up especially so, and mostly by happy coincidence.

Back in February, following my initial visit to Wermland Opera in Karlstad to hear the world premiere of Tebogo Monnakgotla’s song cycle Sœurs du silence, I immediately booked a ticket to see their production of Giacomo Puccini’s modern classic, Tosca. While I of course am familiar with the opera, I had not yet seen or heard it in its entirety and I looked forward to experiencing Wermland Opera’s apparently rather controversial take.

Daniel Kramer, the award-winning American director of Wermland Opera’s Tosca, talks in the programme book about the titular heroine Floria Tosca as a kind of Marilyn Monroe figure: “a peasant girl who wanted to make it, and did everything she thought she had to do, including sleeping her way to the top”. Kramer also mentions how his perspective as a queer man influences his direction. Indeed, there was plenty of both suggested as well as explicit homoeroticism and sexualisation in general in both the acting as well as the staging. Two examples of this stood out particularly, to me.

One, how the sadistic antagonist Scarpia’s chambers included faux-marble statues: one of a crouching, diminutive female figure on top of a trolley, secured with tie down straps in a bondage-like way, positioned next to a muscular male statue with an engorged penis in a way suggesting the female was performing fellatio.

Additionally, when Scarpia’s henchmen have captured Tosca’s lover, Mario Cavaradossi, they are about to torture him by way of anal rape with a black tonfa-like baton. Up until that point, in the same scene, the jailor had been suggestively fondling and licking that same baton in the background of the stage, in what came across to me as a bit of entirely unnecessary overacting.

The staging and direction were replete with similarly vulgar, violent and/or sexualised symbolism. It brought to mind the similarly celebrated and controversial director and renaissance man, Pier Paolo Pasolini, who used the grotesque as a vehicle for socio-political critique in a manner I suspect Daniel Kramer and the stage and costume designer Carlos Soto were going for. However, instead of shocking me into reflecting on sanctimonious, fascist-adjacent wannabe-dictators, it came across as overwrought and crass. In my opinion, it should either have been dialled back – cutting out some of the degradation and perversion to make the remainder more pointed and effective – or, they should have gone completely off the rails – with buckets of theatre blood, explicit nudity, and viscera galore. In other words, they went either too far – or not far enough.

I thought Camilla Lundberg put it well in her review for Dagens Nyheter: “If its messaging is needlessly loud, at least Tosca keeps the musical pressure at the boiling point, like Puccini requires. […] There are plenty of musical highlights with Daniela Musca in the pit – a genuine Italian opera conductor, appreciated among Scandinavian orchestras. […] It is a peculiar but exciting Tosca with great visual power. Definitely worth seeing, in spite of the occasionally contrived ideas.”

I agree completely about the musical qualities. The orchestra played excellently and I particularly enjoyed the two leads, Adam Frandsen as Cavaradossi and AnnLouice Lögdlund as Tosca, as well as Kosma Ranuer Kroon’s diabolical and depraved Scarpia. It was also an unexpected delight to see and hear Caspar Engdahl – whom I went to school with, way back when! – as the fugitive Angelotti, and in the chorus, dear Erik Arnelöf whom I’ve had the pleasure of singing with in Ensemble Villancico.

Such was my Saturday night. Like I told my dear fiancée on the phone afterwards, I would much rather Wermland Opera try something different, like this, rather than a simple rehash or middle-of-the-road interpretation. While I personally disagree with parts of the execution, I am certainly curious about what Wermland Opera will do next and will continue to follow them expectantly.

Last week, out of nowhere I got a text from a friend of mine about an all-night concert in Stockholm on Friday night, the night before Tosca in Karlstad. It was a triple act arranged by URUK, Uruppförandeklubben (the “Premiere Performance Club”), a volunteer organisation with the aim of getting more contemporary art music out of the desk drawer and in front of audiences. A noble cause if there ever was one! The evening featured three ensembles with varied repertoire, including several world premieres by Swedish composers.

It will probably surprise no one who knows me that my personal highlight of the evening was the vocal ensemble VoNo, performing works by two composers new to me – Vox in Rama by Henrik Dahlgren and Planet Woman Birgitta Flick – as well as Ann-Sofi Söderqvist’s Crossroads which I’d had the pleasure of hearing (and seeing!) once before. VoNo’s twelve singers (eleven this particular evening) were in excellent tune with each other, not only in terms of pitch but also rhythm and interpretation. Add to that their signature simple but effective choreography and staging, and it was equally unsurprising that VoNo drew probably the most passionate responses from the audience.

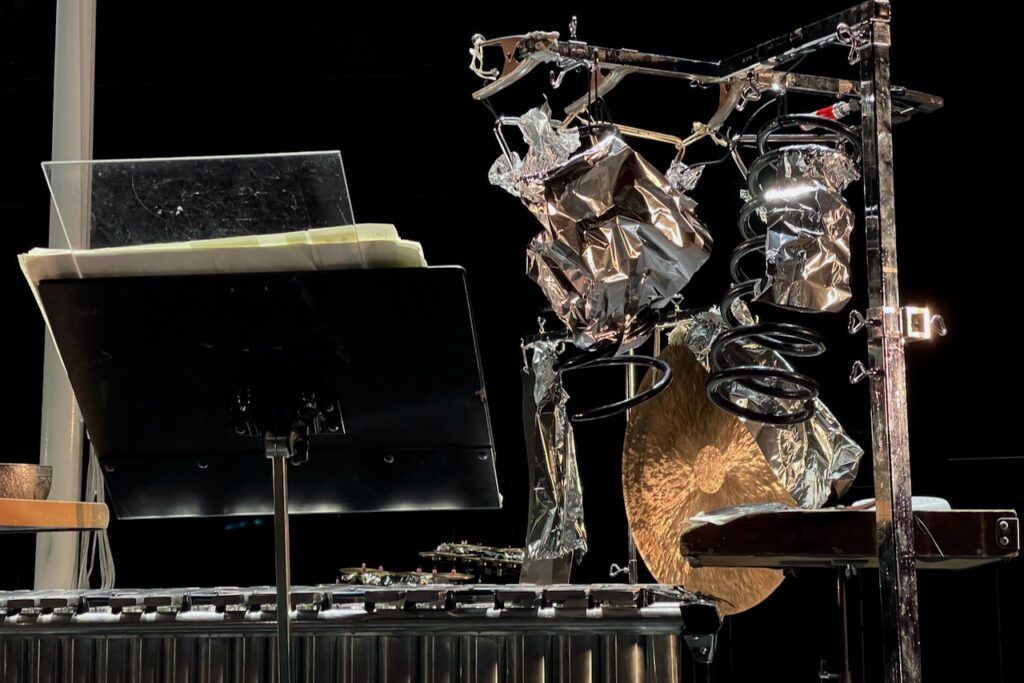

Pianist Mårten Landström and percussionist Magdalena Meitzner opened the evening with a world premiere by Meitzner herself, as well as works by Frej Wedlund and French composer Franck Bedrossian. Metizner and Landström have been playing together since 2022 and want to “erase the borders between the instruments and the musicians, by treating the piano entirely or in part as a percussive instrument”. In effect, this meant using various tools and objects to scrape, strike or otherwise elicit unexpected sounds from the poor Bösendorfer on stage. By the end of the duo’s set, the grand piano sounded audibly out of tune in several spots, not unlikely caused by the duo’s aggressive performance.

At the start of Franck Bedrossian’s piece, Edges, Meitzner played with a bow on a piece of polystyrene foam packaging, producing a physically painful scratching noise. I noticed other listeners reacting similarly, some even making audible sighs of relief when Meitzner put the bow back down. In the programme, Landström described Edges as variously inspired by styles ranging from musique concrète to rock music. I would honestly like to know how Bedrossian relates to rock music because it evaded me entirely. It may very well be my own fault for insufficient understanding of this music, but the comparison came across as uninformed and prejudiced, rather than a profound and intelligent link between radically different styles. (Again, I would happily be proven otherwise.)

Rounding out the evening was Ensemble neo, formerly known as Norrbotten NEO. They opened with a world premiere by American-born, Swedish-based composer Matthew Peterson: Empire Builder, inspired by the long-distance passenger train of the same name going between Chicago and Seattle. It was a brash, loud and above all fun piece that seemed to amuse the performers as much as the audience, if not more; it warmed my heart seeing cellist Nick Shugaev grin like a child at Christmas, drumming out the intense rhythmic backbone with excellent precision together with pianist Mårten Landström, back at the same now-detuned instrument as before.

Yesterday evening, my music-filled weekend ended with a magnificent concert at Oscarskyrkan in Stockholm featuring the Eric Ericson Chamber Choir and the chamber choir of Stockholms Musikgymnasium (the “music high school of Stockholm”), with their respective music directors, Fredrik Malmberg and Sofia Ågren. The high school choir excelled, particularly in Jaakko Mäntyjärvi’s wonderfully suggestive Canticum calamitatis maritimae. They also premiered a setting of the In paradisum text by Benjamin Staern. It was the first choral piece of his I’d heard, and if anything, it made me want to hear more.

Following Bach’s motet Singet dem Herrn, the two choirs united in an encore: a traditional song about the great, transboundary river Dnieper which, as told by Sofia Ågren in her succinct presentation, not only runs through Ukraine but also through Russia – and this will continue regardless of what foolish acts we humans may perform. Ågren led the two choirs in a performance that started out soft as a lullaby, rising gradually to a commanding, terrific rendition, before easing out again, all in perfect unity. As it should be.